Asylum Experience

Life in the asylum

Societal understandings of mental disorders during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were marred by superstition, ignorance, and prejudice. The public’s perception of mental illness ranged from fear to fascination, leading to a widespread misunderstanding of those afflicted and the treatments they endured. Asylums became synonymous with institutionalization and confinement. The daily routines, social dynamics, and interactions between patients and staff reflect the delicate balance of power, compassion, and neglect that defined life within these institutions.

The Epsom Cluster, of five asylums, operated as a small town with its own central electricity generating plant, water towers, and farm. The Cluster was surrounded by greenery, with rural Epsom synonymous with aristocratic leisure activities, spa treatments and agriculture. Bucolic landscapes and horticulture played a significant part in the lives of the patients, with Clare Hickman explaining how:

“a mild regime centres on the placement of the patient in a carefully designed environment, and away from the conditions that had caused him or her to become ill. This form of therapy was based on the idea that the institution itself could play a part in the re-education of the patient … extensive gardens were of vital importance.”[1]

Whilst the setting shaped the patients’ admission, their occupation was also a defining part of their time in the asylums.

Work in the wards

Patients were encouraged to work, with reference to ‘useful employment’ being found in case notes, hospital administrative records, and medical reports as an indicator of whether the patient was fit or capable. Men typically worked in the gardens, the farm or dairy, and in the laundry and kitchens – which aided the self-sufficiency of the hospitals and might even generate revenue when sold on.

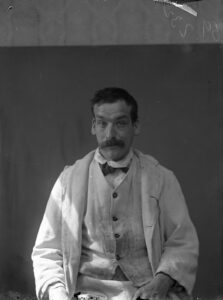

Whilst women also worked in the laundry and kitchens, they most typically were employed in sewing rooms using needlework to make and mend clothes and fabrics for the hospital. These can be seen in the Manor patient photos where they often had two images, the first was untidy and distressed and taken on admission, in the second they are neatly dressed and the photo was taken when discharged – ‘Relieved’ or ‘Recovered’. In Maria Milton’s notes, it is recorded that she is ‘delusional’ as she believes herself confined to the asylum solely for her much-praised needlework. This vignette shows us how whilst certain types of (gendered) occupation, and their physical demands, were intended as therapeutic for patients but were also invaluable for the maintenance of these institutions.